This is the first of a series of posts on Mere Christianity by C. S. Lewis.

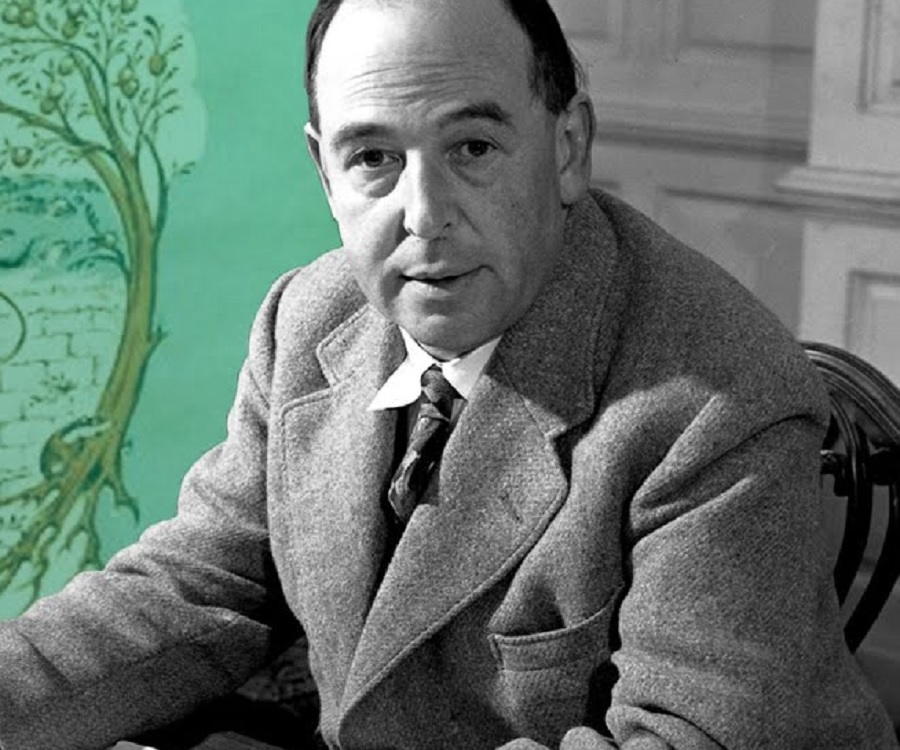

Some six months ago, the Catholic Thought Book Club read C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity. Clive Staples Lewis (1898 – 1963) was a novelist and Christian apologist from Oxford University and was highly influential in the Catholic revival in England. Now Lewis was not a Catholic but he must have been a High Church Anglican because he shares close to a Catholic worldview. He was friends with J. R. R. Tolkien, who was Catholic, and they were part of a group at Oxford made up of Catholics and Protestants who called themselves the Inklings. The Inklings shared their writings and critiqued each other. While Tolkien was known for his Lord of the Rings, Lewis was known for his Chronicles of Narnia series, his science fiction novels, and his works of apologetics.

Mere Christianity was initially an explanation of the faith to the British public over a series of BBC radio broadcasts during the World War II years of 1941 to 1944. The book does not delve into the areas where Christian sects might disagree, but explain the fundamentals of why there is a God and why the Christian understanding of that God makes the most sense. After the BBC broadcasts, Lewis compiled the discussions and published it as a book after the war in 1953. The book is divided into four “Books,” each having a number of chapters. The total number of chapters add up to thirty-three. Here is the table of contents.

Preface

BOOK I. RIGHT AND WRONG

AS A CLUE TO THE MEANING OF THE UNIVERSE

1.The Law of Human Nature

2.Some Objections

3.The Reality of the Law

4.What Lies Behind the

Law

5.We Have Cause to be

Uneasy

BOOK II. WHAT CHRISTIANS

BELIEVE

1.The Rival Conceptions

of God

2.The Invasion

3.The Shocking

Alternative

4.The Perfect Penitent

5.The Practical

Conclusion

BOOK III. CHRISTIAN

BEHAVIOUR

1.The Three Parts of

Morality

2.The “Cardinal Virtues”

3.Social Morality

4.Morality and

Psychoanalysis

5.Sexual Morality

6.Christian Marriage

7.Forgiveness

8.The Great Sin

9.Charity

10.Hope

11.Faith

12.Faith

BOOK IV. BEYOND

PERSONALITY: OR FIRST STEPS IN THE DOCTRINE OF THE TRINITY

1.Making and Begetting

2.The Three-personal God

3.Time and Beyond Time

4.Good Infection

5.The Obstinate Toy

Soldiers

6.Two Notes

7.Let’s Pretend

8.Is Christianity Hard or

Easy?

9.Counting the Cost

10.Nice People or New Men

11.The New Men

The book is structured as (1) why there is a God, (2) what Christians believe about that God, (3) moral behavior as a result of that God, and (4) the nature of this God.

If you wish to read Mere Christianity online, you can access it for free in several different formats here.

I’m going to summarize the major sections and highlights and present some of our conversation it proves enlightening.

Summary

Book

I

Chapter

1: The Law of Human Nature

There is a universal law of human nature—the law of right and wrong—and we intuitively know this law even if we fail to follow it.

Chapter

2: Some Objections

Objections to this moral law include the law as an innate instinct, and the law as a social convention; neither are satisfactory explanations.

Chapter

3: The Reality of the Law

The law of right and wrong is not a law we all follow, but a law we all know we ought to follow it.

Chapter

4: What Lies Behind the Law

Men find themselves under this moral law, a law they did not make but know they ought to obey.

Chapter

5: We Have Cause to be Uneasy

The moral law could only have been put in us by something outside of humanity, that is, God.

###

I was impressed with how systematic Lewis was in Book 1. Each chapter built on the previous. I could see it as stepping toward his conclusion. I put this together as to what I thought the steps through Book 1 consisted. I think it could serve as a summary:

Steps through Book 1:

There is an inherent

human nature of the moral law.

This moral law cannot be

explained by the two objections of instinct and of social convention.

The law of human nature

is verified across humanity.

There are only two views

of understanding the universe, the materialist view—that is of chance—and the

religious view—that is of a creator God outside the universe.

The existence of the

moral law within man points to something beyond the materialist view of the

universe.

The existence of the

moral law within man points to a “Somebody or a Something behind the moral law.

That Something or Somebody is the Christian concept of God in that it asks us to repent and promises forgiveness.

###

My

Comment:

I just finished Book 1

and found this fascinating. Unlike Thomas Aquinas, CS Lewis does not start with

the first cause argument for God. He starts with the moral law written in human

nature argument, and I have to admit I found it powerful. There are so many

places I would like to highlight, but let me limit it to this paragraph from

chapter 4. I'll break up the paragraph because it's kind of large.

Ever since men were able

to think, they have been wondering what this universe really is and how it came

to be there. And, very roughly, two views have been held. First, there is what

is called the materialist view. People who take that view think that matter and

space just happen to exist, and always have existed, nobody knows why; and that

the matter, behaving in certain fixed ways, has just happened, by a sort of

fluke, to produce creatures like ourselves who are able to think. By one chance

in a thousand something hit our sun and made it produce the planets; and by

another thousandth chance the chemicals necessary for life, and the right

temperature, occurred on one of these planets, and so some of the matter on

this earth came alive; and then, by a very long series of chances, the living

creatures developed into things like us.

The other view is the

religious view. According to it, what is behind the universe is more like a

mind than it is like anything else we know. That is to say, it is conscious,

and has purposes, and prefers one thing to another. And on this view it made

the universe, partly for purposes we do not know, but partly, at any rate, in

order to produce creatures like itself—I mean, like itself to the extent of

having minds. Please do not think that one of these views was held a long time

ago and that the other has gradually taken its place. Wherever there have been

thinking men both views turn up.

It had never occurred to that all views of the universe conflate to one of the two. It has always been so. By the way, he shoots down the hybrid view pretty easily. Yes, that's silly

Casey

Replied:

A bit of a quibble,

Manny. Lewis doesn't shoot down the hybrid view exactly but shuts down those

who reject the implications. There's a sense in which the hybrid idea is

exactly right. Creation is always emerging, striving, evolving but it is truly

doing so, not randomly and conveniently so. It actually strives with purpose

and intent. Purpose and intent are sort of outside-in. They can't be explained

simply by atoms crashing into atoms. A turtle strives for the lettuce. Atoms

don't bump together in a way that appears to be a turtle striving for lettuce.

The idea that there's a bunch of stuff randomly appearing to aim a single something which doesn't exist is where it gets silly.

My

Reply to Casey:

Well, wait a second. This

is what Lewis says exactly:

People who hold this view

say that the small variations by which life on this planet “evolved” from the

lowest forms to Man were not due to chance but to the “striving” or

“purposiveness” of a Life-Force. When people say this we must ask them whether

by Life-Force they mean something with a mind or not. If they do, then “a mind

bringing life into existence and leading it to perfection” is really a God, and

their view is thus identical with the Religious. If they do not, then what is

the sense in saying that something without a mind “strives” or has “purposes”?

This seems to me fatal to their view.

It seems like he's shooting it down to me. I think somewhere in Book I Lewis supported evolution, so he's not against evolution per se.

Casey

Replied to Me:

Let me try this

analogy.... If an arrow is flying through the air toward a target this implies

a shooter. Let's say an "atheist" position would be 'not

necessarily.' The Life-Force position would be yes there is a force behind the

motion of the arrow that we might call a shooter but not necessarily a mind. A

"Theist" position would be that there must be a shooter with a mind

because it is the mind that creates the target.

Once you accept that the

arrow has a target (an aim, a purpose) then you must accept the implication of

a mind. If you reject the mind behind the motion then you must reject the idea

of the target.

The reason for my quibble is that the Theist hybridizes by accepting both the mechanical, emergent elements and the mindful elements simultaneously. The Life-Forcer is hybridizing both to try to keep one foot in each camp but it doesn't work. You must accept the implications in full. It is the rejection of the implications that's problematic.

My

Reply to Casey:

Actually Casey, I think we agree. I'm saying the hybrid is problematic too. And so is Lewis. Anyway, I love your analogy with the arrow. That is a great visual to capture the movement of life and the universe.

Casey’s

Reply to Me:

Oh yes, we agree but I feel it is important to make the distinction about the implications because I think for decades Christians have been so engaged with atheists they've neglected the in-betweeners which is a category that has grown enormously. Probably because the waters have been muddied so much by the Christian-atheist jibber-jabber.

Madeleine’s

Comment:

For me the strongest argument for God is that no one has ever been able to answer how it is possible that anything, living or not, especially human beings with intellect and abilities and a free will, is able to exist in the first place.

My

Reply to Madeleine:

That is also from Aquinas. You can read about the five ways or proofs of God from Aquinas here.

I agree with you

Madeleine. That is the argument that holds the most weight for me too. But I

can understand how Lewis starts with the innate moral law argument. Since

Aquinas science has been so far advanced that most people in the last 200 years

think science can answer everything. If they don't currently have an answer to

how something started from nothing, they expect that some day science will.

I've actually had this come up in a debate with atheists. They argue like this:

"Just because we currently don't know doesn't mean some magic God did it;

science will eventually figure it out."

The innate moral law I think still has holes. I'm not sure he satisfactorily answered the objection to social conventions. It does seem to me that various cultures have different perspectives as to what is morally acceptable. Other cultures might not agree on a Christian moral universe. But I don't know.

Kerstin

Replied to Me:

Manny wrote: " If

they don't currently have an answer to how something started from nothing, they

expect that some day science will.

That's scientism. I know they don't see it, but we're crossing the line between

the physical and metaphysical. The natural sciences, shortened today into

"science", can only show us what you can see and measure according

the the physical realities of this universe. If you take all matter away and

with it all laws governing matter, science becomes obsolete.

I've actually had this come up in a debate with atheists. They argue like

this: "Just because we currently don't know doesn't mean some magic God

did it; science will eventually figure it out."

The infamous "God of the gaps" argument. Once we find the "God

particle" science will explain everything. ;-)

Frances

Comment:

These thoughts of

Benedict XVI when he was the young theology professor Joseph Ratzinger expand

on the religious view: “Finite being, as we experience it, is marked, through

and through, by intelligibility, that is to say, by a formal structure that

makes it understandable to an inquiring mind. In point of fact, all of the

sciences rest on the assumption that at all levels, microscopic and

microcosmic, being can be known. . . The only finally satisfying explanation

for this universal objective intelligibility is a great Intelligence who has

thought the universe into being. Our language provides an intriguing clue in

this regard, for we speak of our acts of knowledge as moments of ‘recognition,’

literally a re-cognition, a thinking again what has already been thought. ‘’

(Bishop Robert Barron, Catholicism, Image Books, pages 67-68)

Kerstin’s

Reply to Frances:

The argument of

intelligibility is simply brilliant.

No comments:

Post a Comment